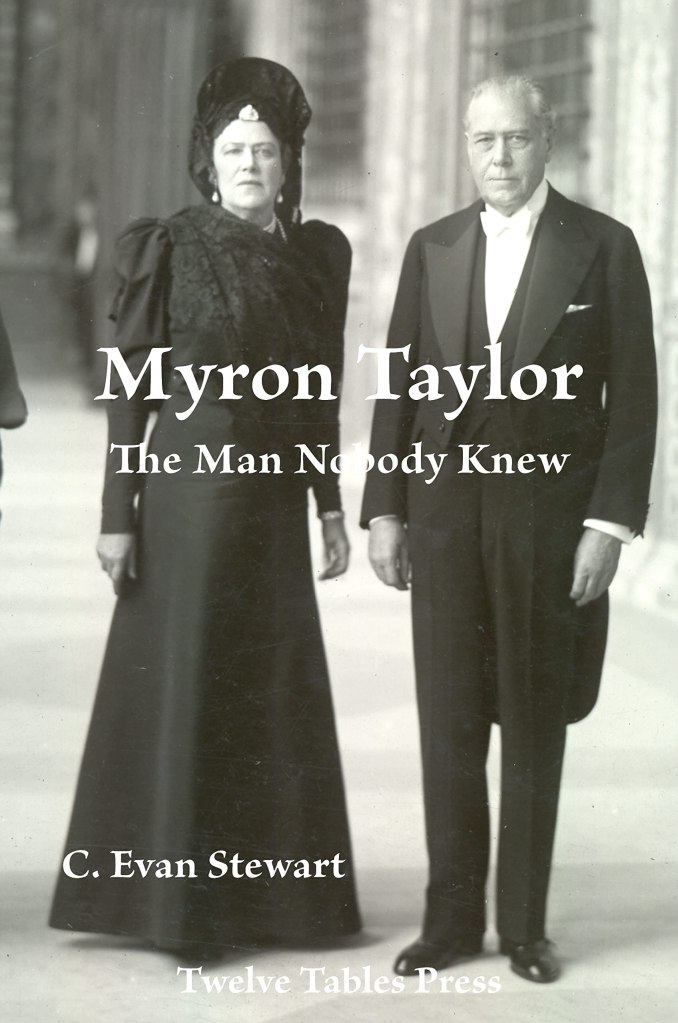

Myron Taylor: The Man Nobody Knew

Read C. Evan Stewart’s work on the man who had a multifaceted career, including President Roosevelt’s Ambassador Extraordinary to Pope Pius XII at the Vatican during WWII.

Order your copy of Myron Taylor: The Man Nobody Knew today.

Stewart is sharing the history of a man who changed the world for the better, who told no one.

Myron Taylor, who had once said that personal publicity should be limited to “a brief mention of birth, marriage and death,”had never been elected to public office and was hardly the leader of the opposition party. He was, however, the Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of the United States Steel Corporation, one of the largest and most important commercial enterprises in the entire world. On December 22, 1939, when President Roosevelt underscored his confidence when he asked Taylor to serve as the President’s “Ambassador Extraordinary” to Pope Pius XII at the Vatican. In the words of one prominent FDR historian, “Taylor was one who really deserved [that] somewhat archaic title.” During the dark and critical times just preceding America’s entry into World War II, Roosevelt informed the Pope: “it would give me great satisfaction to send to you my personal representative in order that our parallel endeavors for peace and the alleviation of suffering may be assisted.” This proposal culminated in the Taylor Mission to the Vatican, which brought Myron Taylor again into the public limelight, but this time as diplomat rather than industrialist. And in his diplomatic role, Taylor grappled with the thorniest issues that arose over the course of World War II. Taylor’s diplomatic contributions to America (and the world) were many and significant, as he was thrust into numerous critical geopolitical matters, including efforts to keep Italy, Spain, and Portugal from entering World War II (as Axis members); helping to secure Lend-Lease aid to Russia (in its darkest hour against the Nazis); efforts to save European Jews and to deal with the Holocaust (and interacting directly with Pope Pius XII in those efforts); ensuring that the Vatican did not oppose the Allies’ unconditional surrender policy; efforts to block Germany from enlisting the Vatican to broker a mediation for the European War; helping to godfather the Bretton Woods Agreement and the creation of the United Nations; and helping Italy to recover after the War. All through his service, his lack of interest in self-promotion stemmed from at least two sources: first, as the reader will see, Taylor was very much a nineteenth-century, Victorian gentleman; and second, Taylor was so successful in everything he had undertaken in his life, he felt no need to convince others of how great he in fact was. Taylor’s lack of a need for public ego-gratification would prove to be of immense importance in fulfilling his diplomatic work, initially for President Roosevelt and later for President Truman. By the time he was representing FDR as the president’s “Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary” to Pope Pius XII, Taylor was no longer “the man nobody knows”―he was, in fact, internationally famous and regularly received world-wide media coverage. But his approach to his task[s] remained the same. Ultimately, the Pope would name Taylor a Knight of the Order of Pius IX, First Degree, in 1948, and President Truman awarded him the Presidential Medal for Merit later that same year. In awarding Taylor the presidential Medal for Merit on December 20, 1948, President Harry S. Truman praised Taylor for having “earned the accolades of his countrymen whom he has served faithfully and well wherever duty called him.” And, upon his death on May 6, 1959, the New York Times, after reviewing his “extraordinary abilities” and his multifaceted career, employed considerable understatement when it concluded that “[h]is was, indeed, a useful life.”